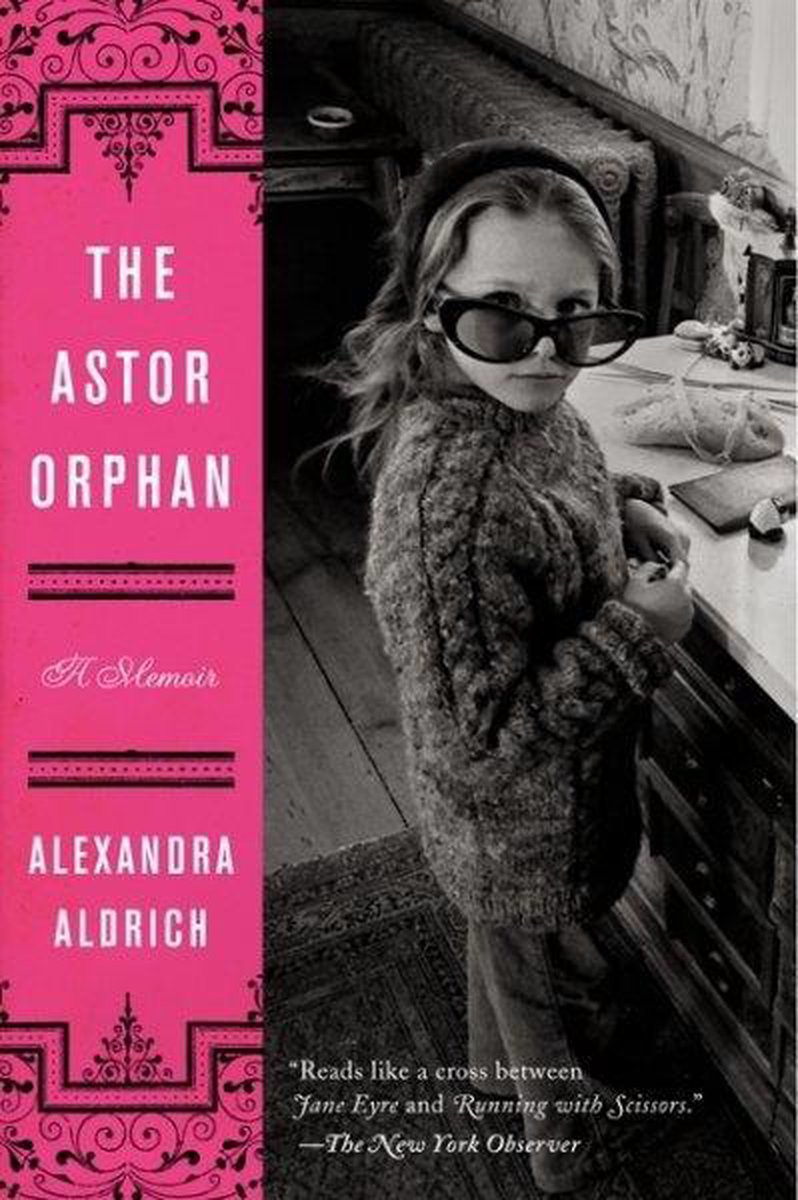

Fans of 'Grey Gardens' — the original 1975 film documentary about Edith 'Edie' Bouvier Beale and her daughter, Little Edie, and the latter-day Broadway and TV movie iterations of the story of eccentric aristocrats living out their days in a decaying mansion — may find themselves drawn to 'The Astor Orphan,' Alexandra Aldrich's new memoir.

They're in for a disappointment.

The Astor Orphan is an unflinching debut memoir by a direct descendant of John Jacob Astor, Alexandra Aldrich.She brilliantly tells the story of her eccentri. Alexandra Aldrich, author of “The Astor Orphan.” Eric Hanson is an illustrator and author in Minneapolis. He recently designed the cover for former Random House editor Daniel Menaker's.

Alexandra Aldrich, a direct descendant of the famous Astor dynasty, grew up in the servants' quarters of Rokeby, the forty-three-room Hudson Valley mansion built by her ancestors. Her childhood was one of bohemian neglect and real privation. But it was fairly stable until the summer of her tenth yea. The Astor Orphan: A Memoir Alexandra Aldrich. Ecco, $24.99 (250p) ISBN 978-0-06-220793-7. A Memoir of a Family House: PW Talks with Alexandra Aldrich; Buy this book In a sparklingly.

This piece first ran in Printers Row Journal, delivered to Printers Row members with the Sunday Chicago Tribune and by digital edition via email. Click here to learn about joining Printers Row.

True, Aldrich delivers buckets of eccentricity, the better to intoxicate her readers with schadenfreude at the spectacle of the mighty brought low. As the daughter of a descendant of the once fabulously wealthy Astor dynasty, the author grew up at Rokeby, the family's 43-room Hudson Valley mansion surrounded by 450 acres of scenic farmland. But in the memoir's timeframe (which is never clearly established, though it seems to be around a quarter of a century ago), the house is dirty and dilapidated. There are brown water stains on the white stucco walls, missing slats in the shutters, congealed grease in the frying pans and mouse droppings in the corners.

The Astor fortune long gone, the family is land-rich but cash-poor, with little Alexandra, who sees herself as an heir to the family's legacy of refinement, forced to live off venison stew, Chinese takeout and the grudging crumbs of her slightly more fortunate relatives. (She and her parents are banished to the third-floor servants' quarters; as she puts it, 'We lived in the eaves.') Though Harvard-educated and multilingual, her bohemian father is ambition-free and unhygienic, always rumbling about the property on a tractor. Her Polish mother, an artist with a pronounced distaste for children, is cold and distant. The family matriarch, Grandma Claire, disapproves of nearly everything — including her son and his farm animals, in particular his prized goats, which go suspiciously missing only to reappear, grimly staring, beneath the icy surface of a frozen lake — but is secretly drinking herself to death.

But unlike the daffy but soulful Beales, the author and her family — at least in the portrait she paints of them — don't have much of an inner life. The dreamy surreality of Edie and Little Edie, who struggle so charmingly to separate the present from the past, is nowhere in evidence here. Instead, Aldrich's Rokeby is a snakepit of petty resentments and backbiting, its residents quirky but unappealing. And the author's oh-poor-me tone, with its near-constant note of petulant grievance and thwarted entitlement, gets wearisome fast. There's no one to like in this story, no one to root for, no one to care about.

Almost as problematic is the fact that the author's all-too-specific rendering of scenes consistently undermines her credibility. To a degree unusual in a memoir that recounts events from a fairly remote past, Aldrich reports pages and pages of realistic dialogue enclosed with quotation marks, which paradoxically makes the reader — at least this one — suspicious of its veracity. (The author anticipates this problem in a prefatory note that only serves to make things worse. 'In some cases, composite characters have been created and time lines have been compressed to retain narrative flow,' she writes. 'I rendered the dialogue as accurately as I could, but as none of it was electronically recorded, I cannot guarantee that it is a word-for-word representation of conversations that took place more than twenty years ago.')

It's admirable, of course, that Aldrich is keen to put us where she was, to force us to see her family history as she saw it, and still sees it. But that's the most fundamental problem of 'The Astor Orphan': its lack of an adult, emotionally mature perspective that would reveal the deeper meaning of events that otherwise remain stubbornly opaque. The greatest memoirs — think J.R. Ackerley's 'My Father and Myself,' Frank McCourt's 'Angela's Ashes' — revisit the lost continent of childhood, so fraught with pain, with the wisdom, tolerance, insight and affection of age. Those authors muse, sift, turn memories over and over in their hands, sharing what they know now, not just what they were able to perceive back then.

Aldrich, on the other hand, seems to know no more now than she did when she was a little girl running through a derelict old house. She's as needy and unevolved as ever, and her memoir thrums with that hunger — for food, for love, for respect, and most of all for payback — on every page. But in the end she leaves her readers just as famished and forlorn, staring up from beneath the ice.

Kevin Nance is a Chicago-based freelance writer whose work appears in the Wall Street Journal and elsewhere.

'The Astor Orphan'

The Astor Orphan Ebook

By Alexandra Aldrich, Ecco, 257 pages, $24.99